Queer Places:

Ardgillan Castle, Ardgillan Demesne, Skerries, Co. Dublin, K34 C984 Ireland

Kensal Green Cemetery, Harrow Rd, London NW10 5JU, UK

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble (27 November 1809 – 15 January 1893) was

a notable British actress from a

theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and

popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes

of memoirs,

travel writing and works about the theatre. She was part of a group of expatriate, largely English-speaking women

which included poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, actors

Charlotte Cushman and

Harriet

Hosmer, mathematician and astronomer

Mary Somerville, inventor

Natalie Micas, painter

Rosa Bonheur, journalist

Matilda Hays, sculptor

Mary Lloyd, journalist and social reformer

Frances Power Cobbe, and others. They were part of an informal organisation of

like-minded women who shared ideas and lives that would later in the

century be called feminist.

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble (27 November 1809 – 15 January 1893) was

a notable British actress from a

theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and

popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes

of memoirs,

travel writing and works about the theatre. She was part of a group of expatriate, largely English-speaking women

which included poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, actors

Charlotte Cushman and

Harriet

Hosmer, mathematician and astronomer

Mary Somerville, inventor

Natalie Micas, painter

Rosa Bonheur, journalist

Matilda Hays, sculptor

Mary Lloyd, journalist and social reformer

Frances Power Cobbe, and others. They were part of an informal organisation of

like-minded women who shared ideas and lives that would later in the

century be called feminist.

Fanny Kemble's address, O Lesbian, to the long dead Sappho, became an

address to lesbians today - O Lesbian, a apostrophic call to a people no

longer absent, dead, or mythic. O Lesbian, the call to share in dialogue. O

Lesbian, still a contested formation; O Lesbian, the apostrophic motion to

animate a people. While Victorian predecessors wrote verse about Sappho and

the tragedy of her love which plunged her into the depths of the sea that was

death, lesbian poets today actually are fulfilling the final intimation of

Fanny Kemble, " 'Tis more than death - 'tis all of life - And parcel of

Eternity."

One of Kemble's special friends was Harriet St. Leger (1795-1878). Harriet St. Leger was unlike any other woman Fanny Kemble had ever met. A member of a reclusive Anglo-Irish country family, she lived at Ardgillan Castle, a fine eighteenth-century manor house set close to the cliffs about fifteen miles north of Dublin.

The daughter of the Hon. Richard St. Leger and a granddaughter of Viscount Doneraile of County Cork, she had lived at the castle for some fifteen years with her sister Marianne and Marianne's husband, a Church of Ireland cleric, at the time of meeting Kemble. Harriet was tall, angular, and athletic, with cropped chestnut hair and fine gray eyes, and eccentric in many things, none more so than in her clothes. Dressed in men's hats and boots especially made for her in London, beautifully cut black and gray cashmere dresses, trim-fitting short waistcoats, and immaculate collars and cuffs, she looked like an androgynous and beautiful young man. To Kemble, she was a modern Atalanta or Diana, the Greek mythology wood goddesses known for hunting and aversion to marriage. To Frances Power Cobbe, the prominent Victorian antivivisectionist and intellectual, who grew up not far from Ardgillan Castle, she was "a deep and singularly critical thinker and reader [who] had one of the warmest hearts which ever beat under a cold and shy exterior." Cobbe adds that Harriet's fondness for male clothing (especially black beaver hats) made her as peculiar in the eyes of her neighbors as the notorious Ladies of Llangollen were in theirs—Lady

Eleanor Butler and Miss

Sarah Ponsonby, learned and literary Regency women who were renowned for living openly as a lesbian couple' According to Cobb; "All the empty-headed men and women in the county prated incessantly" about Harriet's "offensive garments."'

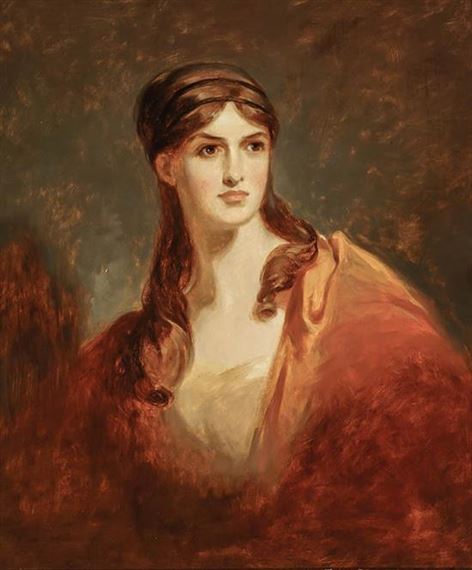

Fanny Kemble

by Sir Thomas Lawrence

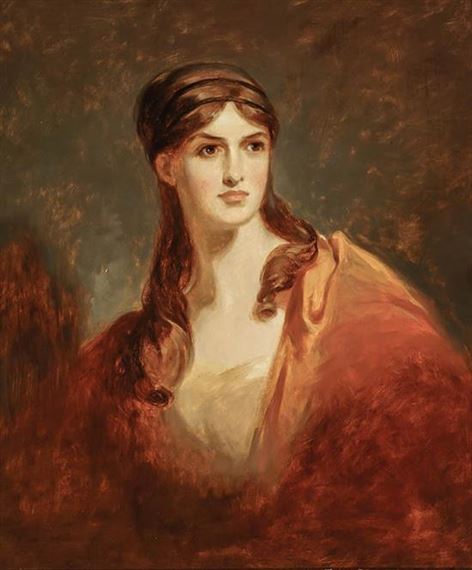

Fanny Kemble

after Sir Thomas Lawrence

hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s

NPG D5156

Fanny Kemble

by Jean Gigoux, printed by Lemercier, after Sir Thomas Lawrence

hand-coloured lithograph, 1830

NPG D5159

.jpg)

Fanny Kemble

by Peter Frederick Rothermel

oil on canvas, 1849

NPG 5462

A member of the famous Kemble theatrical family, Fanny was the eldest

daughter of the actor

Charles Kemble and his

Viennese-born

wife, the former

Marie Therese De Camp. She was a niece of the noted tragedienne

Sarah Siddons and of the famous actor

John Philip Kemble. Her younger sister was the opera singer

Adelaide Kemble.[2]

Fanny was born in London and educated chiefly in France. In 1821, Fanny Kemble departed to boarding school

in Paris to study art and music as befitted the child of, at the time, the

most celebrated artistic family in England. In addition to literature and

society, it was at Mrs. Lamb’s Academy in the Rue d’Angoulême, Champs Elysées,

that Fanny received her first real personal exposure to the stage performing

staged readings for students’ parents during her time at school. As an

adolescent, Kemble spent time studying literature and poetry, in particular

the work of Lord Byron.[3]

One of her teachers was Frances Arabella Rowden (1774-1840?)[4],

who had been associated with the

Reading Abbey Girls' School since she was 16. Rowden was an engaging

teacher, with a particular enthusiasm for the theatre. She was not only a

poet, but, according to

Mary Russell Mitford, "she had a knack of making poetesses of her pupils"[5]

In 1827, Kemble wrote her first five-act play, Francis the First. It

was met with critical acclaim from multiple quarters. Nineteenth century

critics wrote of the script: “…it displays so much spirit and originality, so

much of the true qualities which are required in dramatic composition, that it

may fairly stand upon its own intrinsic worth, and that the author may

fearlessly challenge a comparison with any other modern dramatist.”

[6]

On 26 October 1829, at the age of 20, Kemble first appeared on the stage as

Juliet in

Romeo and Juliet at

Covent Garden Theatre after only three weeks of rehearsal time. Her

attractive personality at once made her a great favourite, and her popularity

enabled her father to recoup his losses as a

manager. She played all the principal women's roles of the time, notably

Shakespeare's

Portia and Beatrice (Much

Ado about Nothing), and

Lady Teazle in

Richard Brinsley Sheridan's

The School for Scandal.[7][8].

Kemble disliked the artificiality of stardom in general, but appreciated the

salary which she accepted to help her family which was often in financial

trouble.

In 1832, Kemble accompanied her father on a theatrical tour of the United

States. While in Boston in 1833, she journeyed to

Quincy to witness the revolutionary technology of the first commercial

railroad in the United States. She had previously accompanied George

Stephenson on a test of the L&M prior to its opening in England and described

the tests in a letter written in early 1830. The

Granite Railway was among many sights which she recorded in her journal.

In 1834, Kemble retired from the stage to marry an American on 7 June,

Pierce Mease Butler, whom she had met on an American acting tour with her

father in 1832.[2]

Although they met and lived in Philadelphia, Butler was the grandson of

Pierce Butler, a

Founding Father, and heir to a large fortune in cotton, tobacco, and rice

plantations. By the time the couple's daughters, Sarah and Frances, were born,

Butler had inherited three of his grandfather's plantations on Butler Island,

just south of Darien, Georgia, and the hundreds of people who were enslaved on

them. After living in Philadelphia for a time, Butler became heir to the

cotton, tobacco and rice plantations of his grandfather on Butler Island, just

south of Darien, Georgia, and to the hundreds of slaves who worked them. He

made trips to the plantations during the early years of their marriage, but

never took Kemble or their children with him.

In the 1840s and 1850s, the Berkshire town served as a cultural center for

Boston-based writers and intellectuals, including

Herman Melville,

Oliver Wendell Holmes,

Henry Ward Beecher, and

Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was also a magnet for an

international coterie of progressive women reformers, among them

Frances Ann

(Fanny) Kemble, the British actress turned abolitionist;

Harriet Martineau,

the British writer on women’s rights; Fredrika Bremer, the Finnish feminist;

and Anna Jameson, the

British feminist and historian—all of whom engaged the young minds at the

Elizabeth Sedgwick’s Lenox Academy, a progressive boarding school in the

Berkshires for audacious girls. At

Catharine Sedgwick’s

invitation, Kemble first visited Lenox in 1838. In her youth, Kemble had

inherited the mantle of her famous thespian aunt, Sarah Siddons. A reluctant

performer, she pursued a theatrical career for a short time before marrying

the Southern American aristocrat Pierce Butler and retiring from the stage in

1834. The marriage proved disastrous; the couple became estranged in 1842 and

finally divorced in 1849, at which time she settled in Lenox. Characterizing

her “sisterhood” with Kemble in the strongest of terms, Sedgwick wrote: “I do

not believe that men can ever feel so pure an enthusiasm for women as we can

feel for one another—ours is nearest to the love of angels.” In Lenox,

Sedgwick, Kemble, and the young Hosmer formed a close bond. A few years later,

Hosmer would attribute her decision to pursue a sculptural career to her

friendship with Kemble.

Demonstrating an intrepid independence, Kemble became Lenox’s most

conspicuous resident. She caused quite a stir by adopting the revolutionary

dress of pantaloons, thus participating in the short-lived yet quite radical

Dress Reform Movement promoted by Amelia Bloomer. Kemble loved to ride her horse through the countryside,

her riding habit consisting of a black velvet jacket and cap and a wide white

riding skirt with man’s trousers beneath. Writing in the journal the Lily,

Bloomer noted that “male attire” had become prevalent among certain women in

Lenox: “Several ladies of Lenox with Mrs. Kemble at their head, had actually

paraded the streets, equipped in coats, vests and pantaloons, and all the

other paraphernalia of a gentlemen’s dress.”

At Kemble's insistence, the family spent the winter of 1838–39

there and Kemble kept a diary of her observations, flavored strongly by the

abolitionist sentiment. Kemble was shocked by the living and working conditions of the

slaves and

their treatment at the hands of the overseers and managers. She tried to

improve conditions and complained to her husband about

slavery, and about the

mixed-race slave children attributed to the overseer, Roswell King, Jr.

When the family returned to Philadelphia in the spring of 1839, Kemble and

her husband were suffering marital tensions. In addition to their

disagreements over treatment of the slave families at Butler's plantations,

Kemble was "embittered and embarrassed" by Butler's marital infidelities.[10]

Butler threatened to deny Kemble access to their daughters if she published

any of her observations about the plantations.[11]

By 1845-7, the marriage had failed irretrievably, and Kemble returned to

Europe.[2]

Butler disapproved of Kemble's outspokenness, forbidding her to publish.

The relationship grew abusive, and Kemble eventually went back to England with

her two daughters. Butler filed for a divorce in 1847, after they had been

separated for some time, citing abandonment and misdeed by Kemble.[1]

In 1847, Kemble returned to the stage in the United States, as she needed

to make a living following her separation. Following her father's example, she

appeared with much success as a Shakespearean reader rather than acting in

plays. She toured the United States. The couple endured a bitter and

protracted divorce in 1849, with Butler retaining custody of their two

daughters. At that time, with divorce rare, the father was customarily awarded

custody in the patriarchal society. Other than brief visitations, Kemble was

not reunited with her daughters until each came of age at 21.[12]

Kemble returned to her acting career as a solo platform performer beginning

her first American tour in 1849. During her readings she rose

to focus her work on the presentation of edited works of Shakespeare, although

unlike others she insisted on providing a representation of his entire canon,

ultimately building her repertoire to twenty-five of his plays.

Fanny Kemble’s sister, Adelaide

Sartoris, who had lived in Rome for two years, led a salon on Wednesday

and Sunday nights in her apartment atop the Spanish Steps. Trained as an opera

singer, she performed regularly at these cosmopolitan gatherings, which

Harriet Hosmer attended with regularity.

Kemble soon followed her sister to Rome, arriving in January of 1853. Hosmer,

enamored with the city and its community of independent women, wrote that the

two Kemble sisters were “like two mothers to me.”

Charlotte Cushman held her

first reception in her new home in January of 1859, beginning a tradition that

would continue for many years. Mingling at this festive event were the

feminist art historian Anna Jameson, Fanny Kemble,

Adelaide Sartoris, and the British author and reformer

Mary Howitt, to name just a few. When the Irish feminist

Frances Power Cobbe came to town, she noted: There was a brightness, freedom and joyousness among these gifted Americans, which was quite delightful to me. Cushman had the gift of drawing out the best from all who came, explained

Emma Crow, the youngest daughter of the philanthropist Wayman Crow.

Fanny Kemble's ex-husband squandered a fortune estimated at $700,000. He was saved

from bankruptcy by his sale on 2–3 March 1859 of the 436 people he held in

slavery.

The Great Slave Auction, at Ten Broeck racetrack outside

Savannah, Georgia, was the largest single slave auction in United States

history. As such, it was covered by national reporters.[13]

She returned to the theatre and toured major US cities, giving successful

readings of Shakespeare plays. Her memoir circulated in

American abolitionist circles, but she waited until 1863, during the

American Civil War, to publish her anti-slavery

Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839.[2]

It has become her best-known work in the United States: she published several

other volumes of journals.

Following the

American Civil War, Butler tried to run his plantations with free labour,

but he could not make a profit. He died of

malaria in

Georgia in 1867. Neither Butler nor Kemble ever remarried.[14]

She performed in both Britain and the United States, concluding her career

as a platform performer in 1868.[9]

Her older daughter, Sarah Butler, married Owen Jones Wister, an American

doctor. They had one child,

Owen

Wister, who grew up to become a popular American novelist, writing the

popular 1902 western novel

The Virginian. Fanny's other daughter Frances met James Leigh in

Georgia. He was a

minister born in England. The couple married in 1871. Their one child,

Alice Leigh, was born in 1874. They tried to operate Frances' father's plantations with free labour, but

could not make a profit. Leaving Georgia in 1877, they moved permanently to

England. Frances Butler Leigh defended her father in the continuing postwar

dispute over slavery as an institution. Based on her experience, Leigh

publishedd Ten Years on a Georgian Plantation since the Warr(1883), a

rebuttal to her mother's account..

[18]]

Kemble's success as a Shakespearean reader enabled her to buy a home in

Lenox, Massachusetts.[15]

In 1877, Kemble returned to London to join her younger daughter Frances, who

had moved there with her British husband and child. Kemble used her maiden

name and lived there until her death. During this period, she was a prominent

and popular figure in London society. She became a great friend of the

American writer

Henry

James during her later years. His novel,

Washington Square (1880), was based upon a story Kemble had told him

concerning one of her relatives.[16]

Kemble openly discussed Frances

Power Cobbe and Mary Lloyd as a couple.

In an 1877 letter to Harriet St. Leger, published in 1890,

Kemble mused: “I think Mary Lloyd really suffers from London; nevertheless not

half so much as Fanny would from living out of it. They talk of going away,

but . . . I think they are likely to be here for some time yet.” Kemble rented

a house formerly occupied by Lloyd and Cobbe, and whether writing of how Cobbe

had to cancel engagements when Lloyd got lumbago, mentioning that “Fanny Cobbe

and Mary Lloyd are coming to lunch with me on Monday,” or casually referring

to “them,” “they,” and “their” when Cobbe was her primary subject, she took it

for granted that the women were a conjugal unit. Kemble’s vision of the

relationship corresponded to Cobbe’s, who recalled “falling fast asleep while

[Fanny Kemble] was reading Shakespeare to Mary Lloyd and me in our

drawing-room” and whose own autobiography was peppered with references to

“us,” “our house,” and “our neighbors.”

In her Records of Girlhood (1879), Fanny Kemble recalled two sisters with

“beautiful figures as well as faces” who wore dresses “low on the shoulders

and bosom” and wrote of one, “I remember wishing it were consistent with her

comfort and the general decorum of modern manners that Isabella Forrester’s

gown could only slip entirely off her exquisite bust.”

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fanny_Kemble

- Queers in American Popular Culture, Volume 2

by

Jim Elledge

ABC-CLIO, 2010 - Social Science - 945 pages

- Fanny Kemble: A Performed Life

by

Deirdre David

University of Pennsylvania Press, Feb 12, 2013 - Biography & Autobiography - 376 pages

- Marcus, Sharon. Between Women (pp.51-52). Princeton University Press.

Edizione del Kindle.

- Dabakis, Melissa. A Sisterhood of Sculptors . Penn State University

Press. Edizione del Kindle.

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble (27 November 1809 – 15 January 1893) was

a notable British actress from a

theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and

popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes

of memoirs,

travel writing and works about the theatre. She was part of a group of expatriate, largely English-speaking women

which included poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, actors

Charlotte Cushman and

Harriet

Hosmer, mathematician and astronomer

Mary Somerville, inventor

Natalie Micas, painter

Rosa Bonheur, journalist

Matilda Hays, sculptor

Mary Lloyd, journalist and social reformer

Frances Power Cobbe, and others. They were part of an informal organisation of

like-minded women who shared ideas and lives that would later in the

century be called feminist.

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble (27 November 1809 – 15 January 1893) was

a notable British actress from a

theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and

popular writer, whose published works included plays, poetry, eleven volumes

of memoirs,

travel writing and works about the theatre. She was part of a group of expatriate, largely English-speaking women

which included poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, actors

Charlotte Cushman and

Harriet

Hosmer, mathematician and astronomer

Mary Somerville, inventor

Natalie Micas, painter

Rosa Bonheur, journalist

Matilda Hays, sculptor

Mary Lloyd, journalist and social reformer

Frances Power Cobbe, and others. They were part of an informal organisation of

like-minded women who shared ideas and lives that would later in the

century be called feminist.

.jpg)